If you’ve ever laid down to go to sleep at night, and suddenly found that your room is spinning around you, or that your walls appear to be sliding up and down, you may have experienced Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). BPPV is the most common form of vertigo, and it will be obvious to you if you have it. It is triggered by:

- Getting up

- Laying down

- Rolling over

- Looking up

Although very common, researchers don’t know why it happens to some people and not others. Sometimes it can be triggered by an underlying ear condition but this is not the most common cause.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo is a long string of words that defines exactly what it is:

- Benign – it is a non-life threatening condition

- Paroxysmal – short term, the symptoms quickly resolve

- Positional – it only occurs in specific positions

- Vertigo – you see the world spin around you

The Basics

BPPV is a mechanical issue in your inner ear. You can see in the photo below your outer, middle, and inner ear.

Your outer ear refers to the part you can see, and the canal that leads toward your ear drum. It helps us hear by catching sound waves and transmitting them to your ear drum so they can reach your hearing organ, the cochlea. Your ear drum, or tympanic membrane, separates the outer ever from the middle ear. The middle ear is the part inside our ear that regulates pressure. It connects the backside of your ear drum to your throat via the Eustachian tube. This is a vital structure for pressure regulation. At baseline, the Eustachian tube is shut, when you change elevation, or f eel congested, it quickly opens and then shuts again, that open and shut mechanism is what causes your ear to “pop”. Some people can do this on command, it is the same mechanism of pressure regulation. Lastly, deep in our skull, but still connected to our ear, is the inner ear. The inner ear houses two parts, the first is the vestibular system and the second is the cochlea. The cochlea senses vibrations from your outer ear, tympanic membrane, and ossicles. In turn, it sends a signal to your brain, which perceives the sound, turning it into what you hear. Connected to the cochlea is the vestibular system, this organ senses where your head is in space, and is responsible for your feeling of equilibrium.

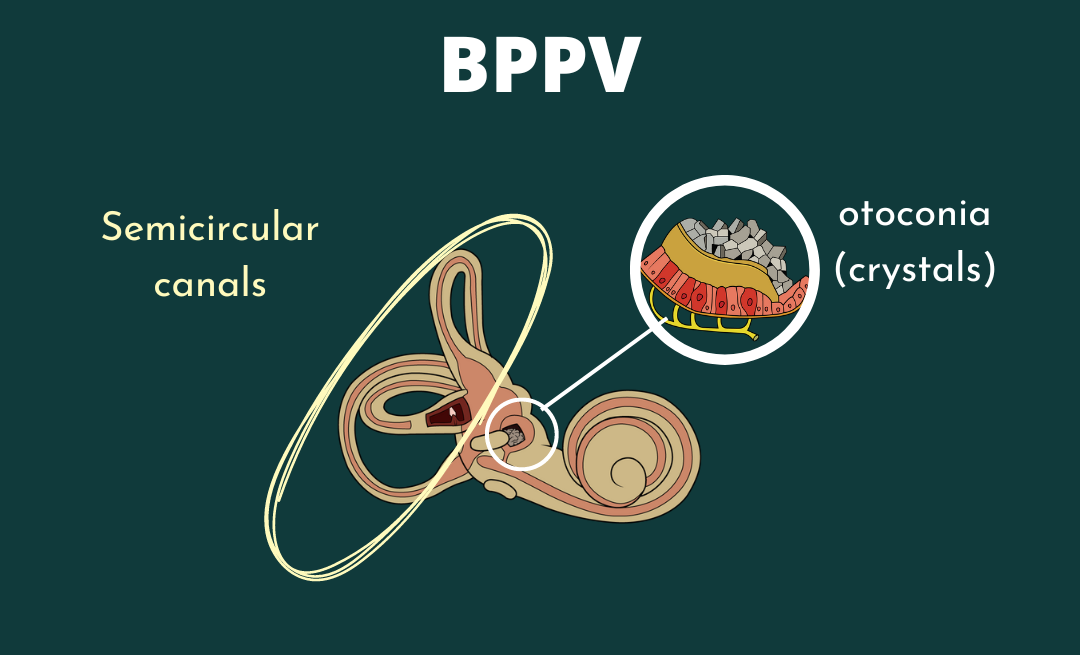

The vestibular system, deep in your skull, is where your BPPV comes from. Within your vestibular system, there are a few parts. The first is the utricle and saccule, which are your otolith organs, the second important structure here are the three semicircular canals. These two systems work collaboratively to ensure you know where your head is in space at all times.

The otolith organs contain tiny calcium carbonate crystals, otoconia. Otoconia, often referred to as ‘ear crystals’, detect linear movement. They are “stuck” like rocks on jelly to a gelatinous layer, which is connected to hair cells. When you look down into neck flexion, the otoconia slide forward with gravity, which pull the hair cells forward, and transmit a signal to your brain via your vestibulocochlear nerve. This happens in all directions that would cause rocks to move with gravity. Through this mechanism, always know where our head is in space when moving linearly. Separately, angular movements like twisting, turning, and moving at an angle are detected by the semicircular canals. Three canals, anterior, horizontal, and posterior, detect motion within those planes. When the systems work together, you should always know where your head is in space.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo are:

- True room spinning/vertigo

- Vertigo that is only in certain positions & lasting less than 1 minute

- Vertigo sometimes associated with nausea and vomiting.

BPPV is frequently misdiagnosed in those who have other types of vertigo or experience chronic dizziness lasting longer than 1 minute.

Why Do I See the Room Spin?

Semicircular canals don’t just detect and transmit motion signals, they are also responsible for your vestibuloocular reflex, or VOR. VOR is the reflex involved with your keeping objects still while you are moving your head. When the vestibular system is working properly, you can easily look left and right, or up and down, quickly, while keeping your eyes still. You can experiment with this by choosing a spot on the wall to stare at, and shaking your head left and right.

VOR is important in order to maintain equilibrium, and our semicircular canals are responsible for making sure it works. When you look left, the fluid in your semicircular canals moves, stimulating the ampulla at the end of the semicircular canal in the plane of movement. That will cause a reflex to be sent through the vestibulocochlear nerve to your brain, to move your eyes in an equal and opposite direction. Then, if you turn back to the right, your eyes will move again, but to the left. This stillness is what keeps our gaze stable when we are walking, and helps us keep our eyes on objects even when we are moving around.

BPPV is what happens when there is an error in the system causing brief spontaneous nystagmus [involuntary eye movement]. The error that occurs is mechanical in nature, your otoconia move off their jelly layer into a semicircular canal. Most often, the otoconia slide into the left or right posterior canal. When this happens, you will experience vertigo that lasts 15-60 seconds and then stops until you move again. The most irritating times of day will likely be getting up in the morning, or going to bed at night. The act of laying down or rolling over in bed often places the canals in a dependent position. The dependent position will force the crystals to move and stimulate the receptors in the semicircular canal that is impacted. This causes the eye to move to correct for the head movement you’ve made. But instead of stopping like it would with your VOR as discussed above, the crystals keep moving because of gravity and inertia. When you have canalithiasis, otoconia are stuck in the canal, the nystagmus is very brief because the rocks settle in the canal and don’t move again until you move your head again. Your canals are sending a signal to your brain that says “we are still moving” even when you’ve stopped, which causes nystagmus.

Diagnosing BPPV:

BPPV is diagnosed based on nystagmus. Nystagmus is incredibly telling because it will move in a very specific direction based on the canal, and the place within the canal, that the otoconia are located. Otoconia can be located in a few different places. The first thing you need to determine is the canal in which the otoconia are residing. All testing for BPPV should be performed with Frenzel or Video Goggles to reduce fixation, an important factor in diagnosis. If your patient can fixate, he or she may be able to stop the nystagmus, which will give you a false negative and will make it more difficult to provide your patient a diagnosis.

It is logical to start by testing the most common canal, the posterior canal. This test is called the Dix-Hallpike (DH).

- Patient sits on the treatment table, close enough to the edge that their head will hang off if they lay backwards.

- Patient turns head to the right 30 degrees

- Patient quickly lays backward and extends head off the table into providers hands at about 45 degrees of extension

- Patient keeps eyes open, the provider watches eyes on screen or through goggles.

- Patient who has positive upsetting torsional nystagmus for 15-60 seconds is positive for Posterior Canal BPPV on the side the head is turned to in the Dix-Hallpike position.

- If positive for Posterior Canal Canalithiasis, treat with Epley Maneuver.

If both sides are negative in the Dix-Hallpike position, check the horizontal canals. To test the Horizontal canals, you perform a Supine-Head-Turn maneuver.

- Patient lays down with neck flexed to approximately 30 degrees, with either a pillow or with assistance of a provider.

- Head is quickly turned left (or right) and left in this position for 15-60 seconds, or until symptoms subside

- Patient keeps eyes open throughout the direction of the test, and the provider should observe eyes to determine the direction of the nystagmus.

- If nystagmus is geotropic, treat with a Bar-B-Cue maneuver to the direction opposite of the “more intense” nystagmus (if nystagmus is more intense on the left test, roll to the right), or try a Gufoni for geotropic nystagmus.

- If nystagmus is ageotropic, treat with Bar-B-Cue maneuver to the direction of the “more intense” nystagmus (if nystagmus is more intense to the right, roll to the right), or try a Gufoni for ageotropic nystagmus.

If all 4 canals are negative for BPPV, but the patient’s subjective interview really makes it seem like BPPV, test for the anterior canal. The head hanging test is for the anterior canal.

- Place the patient on the table close enough to the edge so when they lay back, their head will hang off the edge into providers hands

- Lay back quickly into cervical extension, look for nystagmus.

- Positive test will show down beating nystagmus (with potential torsion) toward the affected ear.

What is the Difference Between Cupulolithiasis and Canalithiasis?

Diagnosing BPPV is the act of determining where the otoconia are stuck within the vestibular system. Otoconia can be misplaced into six different places in either ear. You must determine the affected ear, the canal, and then if it is in the cupula or canal. Within the vestibular system, pictured above, there are the semicircular canals and the ampulla, which houses the cupula. Canalithiasis refers to the otoconia stuck in the semicircular canals. Cupulolithiasis refers to when the otoconia are stuck in the ampullary cupula.

This direction and duration of the nystagmus determines whether you have cupulothiasis or canalithiasis. See the guidelines below for features of each kind of nystagmus and the corresponding diagnosis.

- Right up-beating torsional nystagmus in Right DH position: positive for right posterior canal canalithiasis

- Left up-beating torsional nystagmus in Left DH position: positive for left posterior canal canalithiasis

- Geotropic nystagmus that is more intense in the Left Head-Roll position: positive for left horizontal canal canalithiasis

- Geotropic nystagmus that is more intense in the Right Head-Roll position: positive for right horizontal canal canalithiasis

- Ageotropic nystagmus that is less intense in the Left Head-Roll position lasting >60s: positive for left horizontal canal cupulolithiasis

- Ageotropic nystagmus that is less intense in the Right Head-Roll position lasting >60s: positive for right horizontal canal cupulolithiasis

- Down-beating nystagmus in a head hanging position: positive for ageotropic canal canalithiasis

How to Treat BPPV

Once the correct canal is diagnosed, treatment is relatively simple. Because the otoconia respond to gravity and have likely just slipped into the wrong place, they can be rolled back out, into your otolith organ. The treatment you should receive is completely dependent on the canal that is being affected. Your physical therapist will determine this via a series of tests and watching your nystagmus, the exact diagnosis, and the direction in which you will need to be treated.

- For Posterior Canal Canalithiasis BPPV, you will need to be treated with an Epley Maneuver.

- For Horizontal Canal Canalithiasis BPPV you will need a Bar-B-Cue roll or a Apiani maneuver.

- For Horizontal Canal Cupulolithiasis BPPV you will need a Casani maneuver.

- And for Anterior canal BPPV, you will need a head hanging maneuver.

No matter the kind of BPPV you are experiencing, or how it is treated, it is most important that a professional help assist you with the maneuver. When performed independently, I have found that often times patients put the already displaced otoconia into another canal, instead of back into the otolith organs. Although it is still treatable, it does become more difficult; it is recommended you seek treatment from a physical therapist or ENT first.

Why Me?

Annually, about 1.6% of the population gets BPPV, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%, making It a very prevalent condition (1). Once diagnosed, it is possible that thee BPPV will recur again in the next few years. Although vertigo can be scary and anxiety provoking, once you know what it is, it is easier to self-diagnose and seek proper treatment. Fortunately, it can be treated easily through Canalith Repositioning Treatments as listed above.

Physical Therapy for BPPV

Physical therapists are the main providers who perform Canalith Repositioning Maneuvers, so with BPPV, physical therapists are vital to your treatment! If you are pretty sure this is what’s going on, make an appointment with a vestibular PT today. He or she will evaluate you completely, determine the canal and source of your dizziness, and treat you accordingly! You have direct access to a physical therapist in all 50 states (find one here!), so no need to make an appointment with your primary care physician first.

Source:

(1) Fife, T. D. (2017). Dizziness in the Outpatient Care Setting. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, 23(2), 359-395. doi:10.1212/con.0000000000000450. https://journals.lww.com/continuum/Fulltext/2017/04000/Dizziness_in_the_Outpatient_Care_Setting.7.aspx