Balance is the system our body uses to keep us upright, helps us catch ourselves when we trip, and lets us walk, dance, and run without falling over. Our balance system is constantly being used, even when we are sitting down! There are three systems that make up our balance system. The first is proprioception, the second is vision, and the last is our vestibular system. All three are intricate and purposeful and they all help us with our daily activities.

Proprioception

Proprioception is our internal awareness of where we are in space and how we are moving. Proprioception is used consciously and unconsciously so that we know the angles of our joints, how much force to produce with movement, to sense how and where we are moving, and to sense a change in our velocity. We use proprioception to help us balance constantly, it specifically is helpful when we are on uneven surfaces. Our brain uses constant input from our joints, especially our ankles, knees, and hips in order to keep us upright. When we are on an even surface, like a hardwood floor or smooth concrete, our brain has an easy time keeping us standing up. Our peripheral nervous system (nerves outside the brain and spinal cord) sends signals to our central nervous system (the spinal cord and brain) to tell us where our joints are, and if we need to make adjustments to our posture. When you are on an uneven surface, your joints and peripheral nervous system send signals to your central nervous system to make chronic adjustments so that you don’t trip on the surface. If your brain begins to process this information too slowly or if you receive poor signals for any reason you will have a harder time balancing. If you practice balancing on uneven surfaces your brain will relearn how to balance on all surfaces and you will have an easier time walking on surfaces like carpet, grass, and gravel.

Vision

Being able to see is another important variable in your balance. You may notice that when your eyes are closed or if it’s dark outside you have more trouble standing or walking around. Your visual system provides extra information to your vestibular and proprioception systems to process the information being provided to them. Something as simple as putting on your glasses or turning on the light can drastically improve your balance. Vision is the most relied upon system in our bodies; it is important that we can use vision if we have the option. Going to the optometrist or ophthalmologist is vital if you have visual dysfunction! However, over-relying on your vision can also be dangerous. When we are over-reliant on our vision we don’t utilize the other systems that are important for keeping us upright, our proprioceptive and vestibular systems.

Vestibular

Your vestibular system is an essential part of your balance. Your vestibular system is your inner ear system responsible for balance when you can’t see, can’t feel the floor well, or both! Your vestibular system has its biggest job if you’re walking on grass at night. This system will help your balance, and processing information from the other two systems to adjust your body in space. In practice, we often find that there are many people whose brains have unlearned this system.

Impairment of any of these three systems can lead to poor balance, falls, and the feeling of general unsteadiness. Additionally, some patients with vestibular dysfunction report nausea, dizziness, and swaying when they are still. Many of my patients say that they assume that falling and balance dysfunction is “just a part of aging” and that they should “just get used to it”. On the contrary, balance dysfunction should NOT be a part of aging, and it should NOT be something you just get used to. There are so many ways you can work on your balance, independently or with a physical therapist.

In the clinic there are numerous tests we can use to test your balance. However, in order to differentiate which of your balance systems are not functioning correctly we most often use the M-CTSIB, the Modified Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction in Balance (1). This test measures your balance on 2 surfaces with your eyes both open and closed. In the unmodified version (CTSIB), there is a dome used to provide a visual conflict; this shows whether or not you can intentionally override your vision and use your vestibular system intentionally. However, for most purposes, and ours here, using the modified version is great. Let’s go through how to test yourself if, and when, you find it necessary. Remember to always be as safe as possible when performing this test. I would recommend doing this test with another person nearby and to do it near your countertop or a sturdy chair.

To perform this test you will need a solid surface to stand on, like hardwood or tile floor, and an uneven surface, like balance foam or a couch cushion. You must stand with your feet touching (as close as you can get them) and your arms at your sides, throughout the duration of the test periods.

There are 4 conditions:

- Firm, eyes open

- Firm, eyes closed

- Foam, eyes open

- Foam, eyes closed

For each of the four conditions, you may have three attempts. The time begins when you are set in position, and ends when you complete 30 consecutive seconds or make a mistake. Mistakes include: opening your eyes in a closed condition, taking a step, moving your arms from your sides, or needing assistance to prevent a fall (1). If you, the testee, are able to complete the first round without a mistake, move to the next condition and do not repeat all 3 attempts.

Some sway at the ankles and/or hips, called ankle strategy or hip strategy, respectively, is normal. But, this test shows us which is most difficult for you; the condition that is most difficult is the condition you should work on most in PT. Let’s work through what your test results mean when you finish the test.

Condition 1) while standing in this position, all of your systems are available for balance, but your base of support (BOS) is significantly smaller than you would usually stand. BOS consists of the parts of your body touching the floor beneath you; when it is larger, it is easier to stand, and the smaller it is the more difficult it is to stand (2).

Condition 2) you are able to use your proprioceptive and vestibular systems in this condition. However, you are unable to use your visual system. This tells us that you are very dependent on your vision, and without it you are at an increased risk for falling in situations when you have decreased light, or no vision at all.

Condition 3) in this condition, you are able to use vision and your vestibular system, but it challenges your proprioception significantly. If you have trouble here, it is a sign to work on proprioceptive and dynamic balance in physical therapy.

Condition 4) here, you are mainly able to use your vestibular system to balance. Individuals have most difficulty in this position if they have vestibular dysfunction, and this is frequently something we treat in vestibular therapy.

Fortunately, almost all of the reasons you are experiencing imbalance can be treated in physical therapy. Finding what is difficult for you, and then slowly working on it will improve your balance, reduce your risk of falling, and improve your confidence with your balance!

Sources:

(1) Wrisley, D. (n.d.). Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction on Balance. Retrieved September 07, 2020, from https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/clinical-test-sensory-interaction-balance-vedge

(2) Physiopedia. (n.d.). Base of Support. Retrieved September 07, 2020, from https://www.physio-pedia.com/Base_of_Support

Migraine is a genetically induced hypersensitivity to internal or external stimuli within central nervous system neurons (1). When a neuron that is primed to a migraine, and is triggered by a stimulus either inside or outside of your body, the neuron reacts through a migraine (1). There are treatments for both acute and chronic migraines episodes as well as prevention methods an individual can use to reduce the number of migraines that occur. Migraine is generally considered a headache, however not everyone with migraines experience headaches. Some people get migraines in the form of vertigo, called Vestibular Migraine or Migraine Associated Vertigo. It is estimated that about 1% of the population has Vestibular Migraines (2). Vestibular Migraine often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed for a while before an individual receives a diagnosis of Vestibular Migraine. Some of the symptom and diagnosis criteria will be helpful to pinpoint exactly what’s going on for you specifically. Once you or a loved one is diagnosed with Vestibular Migraines, there are many ways that they can be treated. There is not a quick fix formula for Vestibular Migraine, and finding what works for you may be a process.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

There are many symptoms of Vestibular Migraine and it can present differently in each individual. Using your symptom history and some objective tests to rule out other vestibular disorders, your clinician should be able to come to the diagnosis of Vestibular Migraine if it is right for you. It is important to recognize and remember that many vestibular disorders present similarly, and that migraine could present one way in you, and another in someone else. Logging your symptoms before and during your treatment is a good way to work with your healthcare team toward the right diagnosis. The symptoms include, but are not limited to:

- Severe head pain

- Vertigo with or without head pain

- Photophobia

- Phonosensitivity

- Motion sensitivity

- Neck pain/cervicalgia

- Imbalance

- Spatial disorientation

- Panic and anxiety

- Altered cognition

- Many others depending on the person

- Lightheadedness

- Feeling foggy or off

- Increased symptoms with multi step tasks

- Tinnitus

The symptoms listed above are not the only symptoms patients experience, and you do not need to have headaches to be diagnosed with Vestibular Migraines. Because there are so many ways you can feel dizzy, and sometimes it can be hard to describe to the doctor, I recommend starting a list and showing it to your provider when you have your appointment. This can help you and your healthcare team decide if this is the diagnosis for you.

After a thorouogh history taking, likely from a few practitioners, you will undergo a series of tests. These will differ depending on the individual case, but are generally we are looking to distinguish between multiple vestibular diagnoses. Some combination of vestibulo-ocular, gaze stability, calorics, audiological, positional, functional balance, gait, VNG, and VEMP testing will be employed. A thorough review of all of these tests will tell your providers if you have another vestibular diagnosis that could better account for your symptoms. If no other diagnosis is the most logical, and you fit the International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria, you will receive the proper diagnosis of Vestibular Migraines.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria currently consist of: (4)

- At least 5 episodes of vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity lasting 5 minutes to 72 hours

- Current or previous history of migraines with or without aura according to the ICHD classification

- One or more of the following migraine features with at least 50% of vestibular episodes:

-

- Headache with at least 2 of the following characteristics

- One-sided location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity; photophobia or phonophobia

- Visual aura

- Not better accounted for by another vestibular or ICHD diagnosis

All healthcare providers have access to this diagnostic criteria, and if they can’t find it on the internet, you can always come back and find it here! If you have gone through the diagnostic process and this is you, it’s time to start treating the cause of your symptoms.

Treatment

Once you receive the Vestibular Migraine diagnosis, both prevention and acute treatments become important! Treating your migraines acutely means decreasing symptoms when you have a migrainous episode. Alternatively, treating your migraines preventatively is going to be a constant process and involves dedication from you and your healthcare team. There is no specific protocol for treating Vestibular Migraine, but both anecdotally and in research we have found effective tools for managing symptoms. The combination of acute and preventative treatments, as opposed to doing one or the other, is the most effective way we have found to treat Vestibular Migraines.

Acute treatments are what we call abortive — the concept is to get rid of the attack right as it is happening so it has a decreased impact on your life. These treatments are usually medications. (2, 3, 5)

- Aspirin

- Ibuprofen

- Isometheptene mucate,

- Triptans (Imitrex and Relpax)

- BetaBlockers

- Topiramate

- Triptans

- Benzodiazepines

- Antihistamines

- Timolol eye drops

- Neuromodulation devices

** please remember that medication overuse headache exists, and herefore meds like triptans, NSAIDS, and others in this list can cause rebound attacks!**

These acute treatments are used in response to the onset of a migraine or Vestibular Migraine symptoms. They all work differently, and you should treat your symptoms based on the treatment you find to be most effective with your healthcare team. You may use one, you may use more than one, but these are all tools that you should have around that you likely won’t be using daily. Daily treatments and prevention are going to be specific to you as well, and will become part of your daily routine.

Chronic prevention of your migraines, and treatment of symptoms that are left over from previous attacks, consist of diet modifications, physical activity, and vestibular therapy. Modifying your food and fluid intake is the most valuable and controllable tool you have to prevent migraines and avoid vertiginous symptoms. You can find out more about items to avoid on a migraine diet in a post I wrote here. However, the basics include decreasing sodium, eliminating caffeine, and eating fewer processed foods!

Other preventatives for migrainous symptoms are medications like beta-blockers, anticonvulsants, and SSRI’s (3). Combining diet changes, lifestyle modifications, some medications, and vestibular therapy will help you reduce symptoms and get back to the activities you love most!

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy for Vestibular Migraine is a gradual process of reintroducing irritating stimuli in a way that your brain can recover from quickly. Like most vestibular therapy, your PT will help determine what stimuli your brain has trouble processing and then help you relearn how to process the stimulus. I find that individuals with Vestibular Migraine frequently struggle with patterned carpets, fluorescent lightning, visual tracking, and quick head movements. All of these stimuli can be very irritating, and it’s your therapist’s job to slowly reintroduce them in a way your brain learns is safe and calm. Adhering to your home program is going to be imperative to your success in vestibular rehabilitation. Your brain is very malleable, and you will heal from this given time and proper treatment!

Sources:

(1) Rothrock, J., MD. (2020). What is Migraine? Retrieved September 02, 2020, from https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/what-is-migraine/

(2) Tepper, D. (2015, November 12). Migraine Associated Vertigo. Retrieved September 02, 2020, from https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/migraine-associated-vertigo/

(3)Kramer, J. (2020, August 21). Vestibular Migraine. Retrieved September 03, 2020, from https://vestibular.org/article/diagnosis-treatment/types-of-vestibular-disorders/vestibular-migraine/

(4)Hilton, D. (2020, June 07). Migraine-Associated Vertigo (Vestibular Migraine). Retrieved September 03, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507859/

(5) Wolf, A. (2020, May 08). Acute Treatments for Vestibular Migraine. Retrieved September 03, 2020, from https://thedizzycook.com/acute-treatments-for-vestibular-migraine/

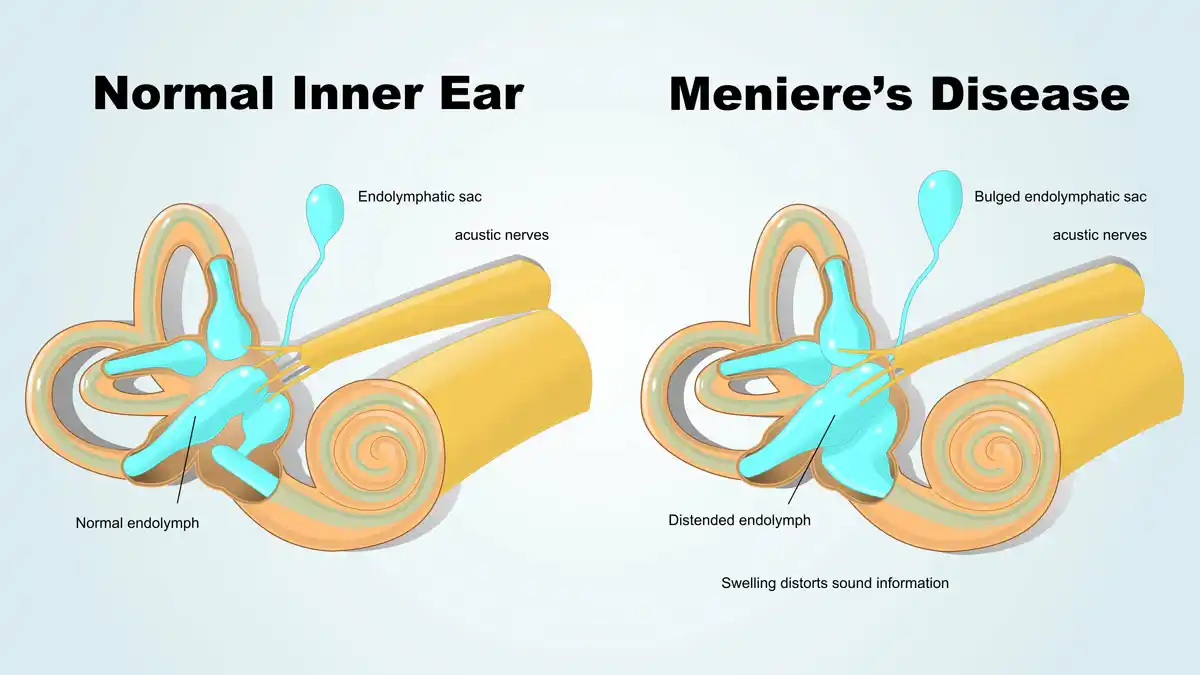

Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops, SEH, is a vestibular system disorder caused by endolymphatic response to an underlying condition (1). In a normal ear, the fluid in your ear is maintained at a homeostatic level to help your balance, hearing, and spatial orientation. If you have Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops, it is likely to be due to an underlying condition. These conditions include, but are not limited to, surgeries that affect the inner ear, inner ear infections, allergies, and head trauma (1, 2). The attacks are spaced weeks to months apart, and over time can destroy your balance and hearing organ slowly. These symptoms manifest in a few different ways depending on the individual. Regardless of your symptoms, we need to treat the symptoms and the root of the problem simultaneously to preserve your vestibular system and restore homeostasis in your body.

The fluid in your ear, endolymph, contains sodium, potassium, and a fluid-like substance. This fluid maintains the correct pressure in your vestibular organ (the inner ear) and helps your balance and hearing function. Too much sodium causes the pressure in your endolymph to increase significantly, leading to an overall pressure change in your inner ear. This pressure fluctuation causes your dizziness and imbalance symptoms. This can be treated by limiting your sodium intake, or limiting other dietary factors that may increase symptoms. Remember, it is not the act of moving your head that causes the fluid to fluctuate; it is other factors like diet, fluid intake, and sodium intake that cause pressure and fluid fluctuations in your inner ear.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

A flareup of Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops is secondary to another injury or dysfunction, and presents differently between each individual. Symptoms that I frequently hear are:

- Episodic vertigo and the sensation of spinning

- Tinnitus

- Chronic or acute imbalance

- Aural fullness

- Temporary or sustained hearing loss

These symptoms tend to last for 8-36 hours. It may cause you nausea and force you to stay in bed during the duration of the episode. Over years of attacks, your hearing can slowly be lost, so it is important to treat it properly once you receive a diagnosis.

To diagnose Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops, your physical therapist, or other healthcare provider, will need a thorough history of your symptoms, patterns, and observations. The patterns of your symptoms provide a clear diagnosis because there are usually triggers that affect the flare ups.

Triggers of Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops usually include:

- Salt or sugar

- Alcohol

- Coffee/caffeine

- MSG

- Nuts and nut butter

Knowing your triggers, the source of your symptoms, is important to treating SEH through conservative measures.

Another tool your healthcare team can use are a series of diagnostic tests. Electrocochleography, or EcoG, is a test for the vestibulocochlear nerve function, and if it is positive, supports the diagnosis of SEH. Audiometry can also support an SEH diagnosis; this is a hearing test to see if you have unilateral hearing loss. Lastly, new research has shown that an MRI with contrast shows definitively if you have either SEH or Ménière’s Disease, however it cannot differentiate between the two. Because a thorough history and clinical diagnosis is typically very accurate, diagnostic testing is not incredibly common or always necessary (1). Once you receive a diagnosis, it’s important to begin treating both your symptoms, and the root of the symptoms, in order to preserve your vestibular system and decrease your symptoms.

Treatment

Treating Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops is very important in order to preserve your vestibular system and prevent future SEH episodes. This can be done through numerous conservative avenues. The first way to treat SEH is through dietary restrictions, the hydroptic diet (1). One of the biggest triggers, and the first thing we typically advise to limit, is sodium. Sodium shows up in our diets more than we think. It is more than just salting our meals, it is in sports drinks, dehydrated foods, ketchup, and sparkling water, just to name a few. Be wary of the presence of salt in your diet, and try your best to limit your intake significantly as too much can cause a large fluid fluctuation and induce an episode. Another common trigger is caffeine (1). Caffeine is the start to your day for many people — whether it is in tea or coffee, most people drink it daily. Caffeine can cause increased symptoms of tinnitus and is a diuretic, which causes fluid loss through urination, therefore disrupting our homeostasis. Following the diet recommended for those with Vestibular Migraines is incredibly effective as a treatment for Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops.

Another, slightly less conservative option is prescribing a diuretic. Prescribing a diuretic is different from drinking caffeinated drinks, which are technically diuretics. A diuretic works to maintain fluid homeostasis in your body, specifically in your inner ear. This will help you excrete a sustained amount of water throughout the day, so it is important that you increase the amount of water you drink throughout the day in order to avoid dehydration. Some diuretics may cause you to excrete too much potassium, so be sure to discuss with your physician the kind of diuretic you are prescribed to see if you need to take a potassium supplement.

Treatment for Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops is a process, and finding what helps your symptoms will be different from another person with a similar diagnosis. It is important that you maintain your quality of life by making this a part of your new routine and treating your symptoms effectively for you. Treating your symptoms doesn’t have to feel like it has taken control of your whole life; start small, and work your way into bigger changes if and when they’re necessary.

Physical Therapy

A physical therapist is one of the most qualified providers to help you treat your vestibular dysfunction, specifically Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops, conservatively. Both your acute and chronic symptoms can be effectively managed with your physical therapist. First, getting a hold of your SEH symptoms by adhering to a hydroptic diet is something your vestibular PT will be able to assist you with. Then, your PT can help prescribe you exercises to improve your balance, decrease dizziness, and discuss any anxiety you may have surrounding your new diagnosis. I have found that those diagnosed with Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops can be very fearful about their symptoms and sometimes end up secluding themselves from others and their normal activities. Instead of secluding yourself, work with a physical therapist and your healthcare team to get back to your favorite activities, and to continue living your life.

Sources:

(1) VEDA. (2020, August 07). Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops (SEH). Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://vestibular.org/article/diagnosis-treatment/types-of-vestibular-disorders/secondary-endolymphatic-hydrops-seh/

(2) BC Balance and Dizziness. (n.d.). Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://balanceanddizziness.org/disorders/vestibular-disorders/secondary-endolymphatic-hydrops/

Ménière’s Disease is a chronic, frustrating, and incurable inner ear disease thought to be caused by a buildup of endolymph in the membranous labyrinth of your cochlea and vestibular system (1). This buildup of endolymph causes swelling on the membranous divide between the endolymph and perilymph, the Reissner’s membrane. This imbalance in your vestibular system causes symptoms of vertigo, spinning, hearing loss, and tinnitus. The potassium-rich endolymph flows into the perilymph, causing your symptoms until the membrane heals and the balance is restored (2). Ménière’s Disease is also commonly called Primary Endolymphatic Hydrops. It is different from Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops as it has a rupture of the Reissner’s membrane and causes intermittent and/or sustained hearing loss. Because the hypothesis of the Reissner’s membrane rupturing is solely theoretical, there is a lot of room for research and rethinking the potential mechanism for Ménière’s Disease. However, regardless of the theory, we can treat your symptoms with a good healthcare team.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Ménière’s Disease is associated with many signs and symptoms. It is important to recognize when they occur and differentiate between Ménière’s Disease and other causes of dizziness. The most common symptoms of Ménière’s Disease are: (1)

- Spontaneous, violent vertigo

- Fluctuating hearing loss

- Tinnitus and/or fluctuating hearing loss

The above symptoms occur regularly with Ménière’s Disease, but there are other ways to present as well. The following are less common, but can be frequent: (1)

- Anxiety

- Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting

- Cold sweats

- Heart racing/palpitations

- Blurry vision

- Eye jerking and/or nystagmus, feels like the room is spinning

- Trembling

Some patients know when an attack is about to happen. These symptoms almost mimic pre-migraine symptoms, however this is not a migraine. These include:(1)

- An “aura”

- Decrease balance

- Headache

- Increased inner ear pressure

- Tinnitus

- Hearing loss or sensitivity to sound, usually on one side

- Feeling of uneasiness

Knowing what your pre-Ménière’s symptoms are can help you move to a safer more comfortable space before the vertigo sets in. When you have a Ménière’s attack, try to keep tabs on these as a mental or physical list to be helpful to yourself.

Typically between Ménière’s attacks are asymptomatic, but for some there are symptoms that are lasting or sometimes occur between attacks. These kinds of symptoms tend to vary from person to person. Examples of symptoms are:(1)

- Difficulty concentrating

- Dizziness and/or lightheadedness

- Fatigue or sleepiness

- Sound sensitivity

- Hearing loss on one side

- Vision difficulties (blurriness, decreased depth perception)

- Unsteadiness (imbalance, falling, general stumbling)

The diagnosis of Ménière’s Disease can be complicated as symptoms come and go seemingly at random. There are specific diagnostic criteria in order to diagnose Ménière’s Disease. The following must be met in order to receive a diagnosis: (3)

- Two or more episodes of dizziness lasting from 20 minutes to 12 hours

- Audiometrically measured low- to medium- frequency sensorineural hearing loss in one ear defining the affected ear on at least one occasion before, during or after one of the episodes of vertigo

- Fluctuating aural (ear) symptoms such as tinnitus, hearing loss, fullness, in the affected ear

- Not better accounted for or diagnosed as another vestibular disorder

Clinical tests also address and can help diagnose Ménière’s Disease. These tests are:(4)

- ElectroCochleoGraphy: measures electrical responses in your cochlea

- Audiometry: a hearing test

- Electronystagmography: tests eye movement in response to your ear stimulation with warm water or cold air

The diagnosis of Ménière’s Disease is the first step ini direction to the beginning of your treatment. Although there is no treatment to cure Ménière’s Disease, treating your symptoms can be simple and effective.

Treatment

Treatment for Ménière’s Disease is all about symptom management and improvement of symptoms of dizziness and imbalance. Most of the time conservative care is effective to treat Ménière’s, and surgical intervention is unnecessary. These conservative treatments are most often provided by a physical therapist and your physician. These avenues are dietary considerations, medications, and Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT).

The first step in treatment is the reduction of sodium in a person’s diet. Dietary restriction can be more strict than just reducing sodium, however sodium is usually the best place to start. Other dietary considerations include dairy, gluten, alcohol, and other common allergens and digestive irritants. Adhering to these new dietary restrictions is important in treatment as it will help reduce the risk of Ménière’s attacks recurring more frequently by reducing your overall inner ear pressure fluctuation risk. If this alone is ineffective for you, your physician may prescribe physical therapy and/or medications to help abate your symptoms and control your fluids.

The two most common medications in Ménière’s Disease are betahistine and diuretics. Betahistine is a vestibular suppressant used by those with Ménière’s Disease to suppress the vestibular system without interfering with vestibular habituation or compensation; this is different from Meclizine which both suppresses the vestibular system and interferes with compensation (5). Physical therapy is very effective in treating the vestibular system through CRT. It assists in compensation and habituation, and can treat imbalance; read more about PT below.

The non-conservative options are much less common and are a last resort for those who have frequent and recurring Ménière’s Disease episodes. The first option is an intratympanic gentamicin shot. This injection destroys some vestibular tissue in one ear, therefore decreasing or eliminating the change of a vertiginous episode. There is a risk of significant hearing loss with this option, so be sure to try and consider other things first (6). The other option is a surgical procedure to reduce pressure in the inner ear; this is done very infrequently and is often ineffective.

There are numerous treatments for Ménière’s Disease. Beginning with conservative treatments and working toward more intensive, invasive options is typically what I see in my patients. However, choosing with your healthcare team what is right for you is always the best option.

Physical Therapy

The goal of physical therapy in vestibular disorders is to treat symptoms of imbalance and lightheadedness, especially in those with Ménière’s Disease between attacks. After an episode, it is common for you to be tired, and laying down to recuperate for some time is normal and expected. However, when you begin to feel better it is important that you begin to move around to move your head when you’re feeling better. You just had an attack on your vestibular system, which now is unbalanced and is looking for input to help re-weight itself. By moving your head, you are assisting your vestibular system process and accommodate changing signals. Too much too soon can also be difficult, and you may want help grading your exercises. A physical therapist is the choice of a provider for help, he or she will be able to find exercises that help you rehabilitate your vestibular system in a way that will slowly improve your tolerance to activity and increase your balance. Often, your vestibular system will cause feelings of lightheadedness and nausea, and this can mean we’ve dont too much or not enough. Finding the fine line between the two is vital for a solid treatment plan.

Other Safety Considerations

When balance and mobility problems pop up, trips, and falls are more likely to occur. But many folks don’t realize the full spectrum of potential household hazards that can increase the likelihood of a stumble. With that in mind, NCOA created this guide, Home Safety for Older Adults: A Comprehensive Guide.This actionable PDF checklist that readers can use to ensure they or their loved ones remain safe at home.

This piece includes a wide variety of practical tips and recommendations from senior safety experts, including:

- Seasonal and material considerations for exterior home safety

- Suggestions for accessibility of everyday items

- Products to help older adults age in place safely

Sources:

(1) VEDA. (2020, June 24). Ménière’s Disease. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://vestibular.org/article/diagnosis-treatment/types-of-vestibular-disorders/menieres-disease/

(2) Gibson, W. P. (2017, August 31). Revisiting the Cause of the Attacks of Vertigo During Meniere’s Disease. Retrieved August 30, 2020, from https://www.jscimedcentral.com/Otolaryngology/otolaryngology-4-1186.pdf

(3) Lopez-Escameza, J. A., Carey, J., Chung, W., Goebeld, J. A., Magnusson, M., & Mandalàf, M. (2015, February 10). Diagnostic criteria for Menière’s disease. Retrieved August 30, 2020, from https://content.iospress.com/download/journal-of-vestibular-research/ves00549?id=journal-of-vestibular-research/ves00549

(4) Martel, J. (2013, January 27). Meniere’s Disease: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and More. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://www.healthline.com/health/menieres-disease

(5) Lacour, M., Van de Heyning, P., Novotny, M., & Tighilet, B. (2007, August). Betahistine in the treatment of Ménière’s disease. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2655085/

(6) NIDCD. (2020, July 15). Ménière’s Disease. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/menieres-disease

Mal de Debarquement Syndrome, or MdDS, is a rare and complex syndrome that leaves you feeling like you have sea legs all the time — bobbing, swaying, and losing your balance. Typically when patients come in with this diagnosis they describe it as “I got off a boat, I walked onto dry land, but my legs and brain never feel like I stepped off of the boat”. There are two kinds of MdDS, classic and spontaneous. Classic develops after being in constant passive motion for a long period, and spontaneous MdDS develops without a movement trigger. MdDS is poorly understood, but what we do understand is that it occurs in healthy people who spend long durations with passive motion, such as being on a boat for days at a time, sleeping on a water bed, or being on a long plane flight (1). Those with Mal de Debarquement do not feel true vertiginous spinning, nor do they usually get motion sick. Physical therapy can be helpful for MdDS, but thorough treatment will be multidimensional and combine treatment from many practitioners.

MDDS Symptoms & Diagnosis

Symptoms of Mal de Debarquement are chronic consist of: (1)

- Feeling like you’re walking on uneven ground all the time

- The feeling of bobbing up and down even when you’re still

- Persistent rocking or swaying

- General imbalance

- Feeling better when you’re moving around or passively moving

The experience of feeling better when you are in motion is one of the keys to your diagnosis. There are no clinical tests for an MdDS diagnosis, but a thorough history and good clinical skills from your physical therapist will be able to help you toward a diagnosis.

The diagnostic criteria consist of: (2)

- Clinical history of oscillating vertigo

- Temporary improvement with re-exposure to passive motion

- The symptoms began within 48-hours of disembarking a trip from chronic passive motion (boat trip, plane ride, long duration road trip)

Your diagnosis of MdDS is often frustrating and can be anxiety-provoking. Individuals with MdDS are more likely to have pre-existing anxiety and/or depressive disorders (2). Additionally, migraines and headaches are associated with MdDS and generally increase with the onset of MdDS symptoms(2). Treating all of your symptoms, from rocking and swaying to anxiety is going to be vital to the holistic treatment of Mal de Debarquement Syndrome.

MDDS Treatment

Treating Mal de Debarquement Syndrome can be complex and requires significant commitment from both the patient and providers. According to research, patients treated for MdDS found that the most effective therapeutic for their symptoms was a medication, Benzodiazepines. Common Benzodiazepines are Xanax and Valium, they are used to sedate the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) (2). Additionally, physical therapy and vestibular therapy were found to be somewhat helpful as well. In another study however, they used treatment of the vestibular ocular reflex (VOR) to treat the MdDS symptoms with significant decrease in symptom severity (3). The treatment cited in this article requires a large dome for full visual stimulus, then the patient is seated in a chair and the subject’s head is passively rolled at their rocking frequency while watching the stripes move to the opposite direction of the previously determined affected ear. This treatment was found to be effective immediately after in classic and spontaneous MdDS cases in 78% and 48% of patients respectively (3). In the study’s one-year-follow-up, over 50% of the patients reported that their improvements were lasting (3). A combination of treatments between medications and physical therapy will hopefully treat your Mal de Debarquement Syndrome symptoms.

Physical Therapy(5)

Physical therapy for Mal de Debarquement syndrome is going to be helpful for balance training, gait instability, and sometimes habituation of your vestibular system through Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT). This reflex helps to stabilize your gaze and helps you know where your head is in space. VRT for MDDS is most effective in treating the functional deficits, not necessarily the actual rocking and swaying.

The gold standard for MDDS treatment is the Dai Method (3,4) for visual stimulation with head motion, this is especially helpful in those with classic MdDS. Your physical therapist should work closely with you and your other healthcare providers to assess and provide quality treatment for you specifically. If you have MDDS, this is worth a try as because we can easily access large TV screens or Virtual Reality goggles, this can be reproduced at home with a partner if you’d like to try.

Sources:

(1) National Organization for Rare Diseases. (2020, June 05). Mal de Debarquement. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/mal-de-debarquement/

(2) Cha, Y., Cui, Y., & Baloh, R. (2018, May 7). Comprehensive Clinical Profile of Mal De Debarquement Syndrome. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5950831/

(3) Dai, M., Cohen, B., Cho, C., Shin, S., & Yakushin, S. (2017, May 5). Treatment of the Mal de Debarquement Syndrome: A 1-Year Follow-up. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5418223/

(4) Dai, M., Cohen, B., Smouha, E., & Cho, C. (2014, June 26). Readaptation of the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Relieves the Mal De Debarquement Syndrome. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2014.00124/full

(5) Farrell, L., DPT. (2019, July). Mal de Debarquement Fact Sheet. Retrieved August 29, 2020, from https://www.neuropt.org/docs/default-source/vsig-english-pt-fact-sheets/mal-de-debarquementc0a035a5390366a68a96ff00001fc240.pdf?sfvrsn=7ca35343_0

A concussion occurs when a significant force to your head or body is sustained, leading to a traumatic force to your brain. This sudden and abrupt motion of the brain within your skull can create chemical and mechanical changes within your brain; it is not a bruise, it is a mild trauma (1). Concussions are usually non-life-threatening, but the symptoms are often significant, uncomfortable, and potentially life changing. It is incredibly important to take the time to treat your concussion properly when one occurs, and to protect and prevent your brain against getting one, or multiple, concussions. In the news recently, many people have been discussing Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. CTE is a condition caused by chronic trauma to the brain, leading to a buildup of tau protein in the brain, causing chemical changes in the brain with long term damage (2). Education about signs and symptoms of concussion to coaches, families, athletes, and all other people is so important because the more eyes on people who are at risk the more we can prevent long term damage to everyone’s brain. This is does not occur from one concussion, but repetitive injury to the brain. Treating your concussion is a slow process, you should work with a physical therapist or other qualified healthcare provider to address your symptoms and take the steps to quality rehabilitation.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

A person can typically feel when they’ve had a concussion immediately and if you are an observer, you usually know exactly when a concussion occurs even if you aren’t trained to recognize them. This recognition usually looks like “oh, that looked bad” when someone gets hit in the head. There are two kinds of symptoms related to concussion: observed and self reported.

Symptoms of concussion that are observed by others include: (1, 3)

- The patient not being able to recall the event

- Appearing stunned, dazed, or confused

- Tripping, walking/moving clumsily

- Brief or extended loss of consciousness

- Mood, behavior, or personality changes

Symptoms of concussion that are typically patient reported are:

- Headache or pressure in your head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Imbalance, dizziness, or blurry vision

- Feelings of haziness, grogginess, or sluggishness

- Feeling down, or “not right”

- Changes in sleep, either increased or decreased

Many of these signs and symptoms commonly occur immediately after your injury, but can last for an extended period of time. Testing for a concussion is often a cognitive test, a neurovestibular exam, and potentially scans like a CT or MRI.

The most immediate test for a concussion is a memory test, the ImPACT; for this you need a baseline and a follow up test (3). It tests for IF you have had a concussion, and can be performed if you have taken a baseline measure before beginning your season, this is a common protocol in athletes. Another way to assess symptoms right after injury, and throughout your treatment is a post-concussive checklist, which can be found here (4). Rehabilitating your entire system and all of your symptoms is really important, and dizziness specifically needs to be addressed as well.

Dizziness from a concussion can be a remnant of your injury, and is typically within your vestibular system. This is part of post-concussion syndrome. Post-concussion syndrome is when headaches and dizziness last weeks to months after your initial injury (5). Commonly, post-concussion syndrome patients have vertigo caused by BPPV, episodic dizziness caused by endolymphatic hydrops, concussion induced migraines, or a vestibular hypofunction (6). It is important that if you are having dizziness after a concussion that you seek out proper medical care for treatment.

Treatment

I have frequently heard the following statement from patients, families, and friends: “Oh, I treated my concussion, I just slept for a week and then went back to work”, however contrary to popular belief, this is not how a concussion should be managed. Treatment for a concussion is going to be all about a slow return to your prior level of function, without exacerbating your symptoms. First, yes, you are going to have to rest, but not just laying around your house watching TV. Although physical rest is important, we must also rest our brains. This includes avoiding stimuli like: TV, books, texting, radio, bright lights, and others. Sleep does count as rest, it is a good thing here, but sleeping for a week and then immediately returning to your prior level of function can be dangerous and provoke your symptoms. Slowly returning to your normal activities and rehabilitation can begin after a 14 day period of no symptoms at baseline. Then, you can start to complete physical and vestibular rehabilitation.

Vestibular rehabilitation will be vital as will return to exercise and return to school/work protocols. Vestibular rehabilitation will treat your symptoms such as headache, dizziness, imbalance, and lightheadedness. Physical rehabilitation can be done with a vestibular physical therapist as well, this will help returning to athletic activities, return to work, and return to school. You will be performing brain adaptation, habituation, cardio exercise, and gaze stability. Establishing an exercise program in clinic that you can, and will, perform at home is important to your recovery. The purpose of rehabilitation is to reduce dizziness through repeated exposure to the stimuli that make you dizzy and mildly uncomfortable. These exercises may make your dizziness feel worse for a short period (less than 10 minutes), but continuing to complete these exercises will make you feel better when done properly and consistently.

Rehabilitation is generally performed in 6 steps. This is different for everyone, but for athletes it looks like this:(1)

- Return to general activity, like work or school.

- Light aerobic activity, activity that slightly increases your heart rate, for 5-10 minutes like stationary biking or a short walk

- Moderate activity, activity that increases your heart rate moderately with body or head movement, like moderate weight lifting for less time and intensity than your prior level of function

- Heavy, non-contact activity. This includes activity in all 3 plans of motion, sprints, and heavy lifting

- Practice and full contact, which includes full days of practice that include contact from teammates, however no competition

- Competition and return to function. At this step you may return to your complete prior level of function

It is incredibly important that you work with your healthcare provider to properly grade this plan for you specifically. Throughout these steps, be sure to treat your dizzy symptoms through vestibular rehabilitation while you’re also performing cardio exercise and weight lifting. This can include walking with head turns, VORx1 exercises, and VOR cancellation. Be sure that between each step you have no symptoms for at least 24 hours after your treatment. If symptoms return or increase during treatment, stop and rest; you should return to the previous step when the symptoms stop and you wait until your provider says you may begin again.

Physical Therapy

Treating all of your concussion symptoms is equally important, and a physical therapist is going to be a vital part of your team through this. Vestibular and physical rehabilitation will help your gaze stability, headaches, return to sport, work, and school, and dizziness symptoms. Your PT will help you slowly return to these activities at a graded pace that will be safe and effective while mitigating and treating your symptoms (7). There are many concussion rehab protocols, and your PT will assist you in choosing the right one for you specifically. As a PT, I have seen many patients who believe they have recovered completely, but can’t figure out why they’re still so dizzy. However, treating your dizziness should be a part of your concussion rehab, and it’s why finding a vestibular therapist will be specifically important. A vestibular physical therapist treats dizziness symptoms from any cause, including concussion, and will be able to determine the exact treatment you need to reduce your dizziness. Every concussion is considered serious, and even if you are feeling like you don’t need to you should seek medical assessment to see if you need treatment (8). Concussion treatment is for all people with head injuries, not just athletes.

Sources:

(1) CDC.gov. (2019, February 12). What Is a Concussion? Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_whatis.html

(2) The Concussion Blog. (2019, July 31). What is CTE? Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://theconcussionblog.com/what-is-a-concussion/what-is-cte/

(3) UPMC Sports Medicine. (2020). Concussion Signs, Diagnosis, and Treatment: UPMC. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.upmc.com/services/sports-medicine/conditions/concussions

(4) The Center for Brain Injury Research and Training. (n.d.). Post Concussion Symptom Checklist. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.education.ne.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Post-Concussion_Symptom_Checklist.pdf

(5) Mayo Clinic Staff. (2017, July 28). Post-concussion syndrome. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-concussion-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20353352

(6) Welch, A., Rapaport, L., Upham, B., & Rauf, D. (2018, March 15). What Complications Can Arise From a Concussion?: Everyday Health. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.everydayhealth.com/concussion/what-complications-can-arise-from-concussion/

(7) Stamford Health. (2016, February 9). The Role of Vestibular Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Concussion. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.stamfordhealth.org/healthflash-blog/orthopedic-spine-sports-medicine/vestibular-rehabilitation/

(8) Mucha, A. (2018, March 7). Physical Therapy Guide to Concussion. Retrieved August 28, 2020, from https://www.choosept.com/symptomsconditionsdetail/physical-therapy-guide-to-concussion

Most dizziness comes from somewhere in our ears, however it can also comes from our necks. Cervicogenic dizziness is dizziness the presence of imbalance, unsteadiness, and disorientation that is caused by the cervical spine. This could be your source of dizzy symptoms when other causes of dizziness are ruled out. People with cervicogenic dizziness tend to report that they have a limited range of neck motion, neck pain, and may frequently get headaches. This kind of headache is not to be confused with a migraine, and the symptoms are different than Vestibular Migraines. Most of the time, we are unsure why exactly this occurs, but frequently we associate it with a whiplash injury, or mechanical changes to the cervical spine, degeneration, or inflammation. Other diagnoses that frequently mimic the symptoms of cervicogenic dizziness are whiplash associated disorder, cervical arterial dysfunction, and vertebral basilar insufficiency. At the moment, there are no incredibly specific tests to rule in cervicogenic dizziness, so you need to rely on your symptom history in order to come to a diagnosis.

Symptoms & Diagnosis(1)

Because cervicogenic dizziness doesn’t have a test that rules in the diagnosis, it is imperative to articulate the clarify your symptoms with your PT or other healthcare provider. Symptoms of cervicogenic dizziness last for minutes to hours at a time, and consist of:

- Imbalance

- Unsteadiness

- Lightheadedness

- Disorientation

These symptoms should be consistent with, and related to, pain in the cervical spine. The pain can be at rest, with palpation, with movement, or a combination; additionally the symptoms should subside with interventions that alleviate neck pain.. associated with head movements and cervical spine position changes. This can be hard to differentially diagnose because other dizziness diagnoses are associated with head turns, head position changes, and headaches. The most commonly reported symptom aggravating factors associated with cervicogenic dizziness are:

- Fatigue

- Head/cervical movement

- Anxiety

- Stress

In order to diagnose this properly, it is essential to rule out other diagnoses before landing on cervicogenic dizziness. Other symptoms to consider that may lead to another diagnosis are:

- Aural fullness (feeling of clogged ears)

- Tinnitus

- Oscillopsia

- Cardiovascular factors

- Anything exacerbated by busy environments, positional changes, exertion, or specific activities

In an article by Reiley et.al., authors created an algorithm for diagnosing cervicogenic dizziness, it can be found here!

Treatment(1)

The treatment for cervicogenic dizziness is helping your head and neck relearn spatial orientation. Part of your evaluation should include a manual evaluation of your cervical spine, palpation for tenderness, and assessment of your posture. Oftentimes addressing three things will be the first part of your treatment. Treating this by joint-position-sensation, or neuromuscular re-education is going to be very important. Relocation tasks are the most common form of these, this is frequently done with laser pointers attached to your head.

- Begin in a seated position with a laser pointer headband. The laser should be pointed at the wall, directed at a target in front of you.

- Position your head so the laser is at the center of the target.

- Move your head to the right, and return to center, positioning the laser on the center of the target each time.

- To make this more difficult, perform the exercise with your eyes closed, checking where the laser ends each time.

Physical Therapy (1)

Your physical therapist should be able to both diagnose and treat your symptoms of cervicogenic dizziness. It is important that your physical therapist make the differential diagnosis between other vestibular dysfunction and causes of dizziness, and cervicogenic dizziness. Treating your neck pain and completing neuromuscular re-education will be vital for your recovery and symptom relief.

Source:

(1) Reiley, Alexander S et al. “How to diagnose cervicogenic dizziness.” Archives of physiotherapy vol. 7 12. 12 Sep. 2017, doi:10.1186/s40945-017-0040-x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5759906/

If you’ve ever laid down to go to sleep at night, and suddenly found that your room is spinning around you, or that your walls appear to be sliding up and down, you may have experienced Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). BPPV is the most common form of vertigo, and it will be obvious to you if you have it. It is triggered by:

- Getting up

- Laying down

- Rolling over

- Looking up

Although very common, researchers don’t know why it happens to some people and not others. Sometimes it can be triggered by an underlying ear condition but this is not the most common cause.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo is a long string of words that defines exactly what it is:

- Benign – it is a non-life threatening condition

- Paroxysmal – short term, the symptoms quickly resolve

- Positional – it only occurs in specific positions

- Vertigo – you see the world spin around you

The Basics

BPPV is a mechanical issue in your inner ear. You can see in the photo below your outer, middle, and inner ear.

Your outer ear refers to the part you can see, and the canal that leads toward your ear drum. It helps us hear by catching sound waves and transmitting them to your ear drum so they can reach your hearing organ, the cochlea. Your ear drum, or tympanic membrane, separates the outer ever from the middle ear. The middle ear is the part inside our ear that regulates pressure. It connects the backside of your ear drum to your throat via the Eustachian tube. This is a vital structure for pressure regulation. At baseline, the Eustachian tube is shut, when you change elevation, or f eel congested, it quickly opens and then shuts again, that open and shut mechanism is what causes your ear to “pop”. Some people can do this on command, it is the same mechanism of pressure regulation. Lastly, deep in our skull, but still connected to our ear, is the inner ear. The inner ear houses two parts, the first is the vestibular system and the second is the cochlea. The cochlea senses vibrations from your outer ear, tympanic membrane, and ossicles. In turn, it sends a signal to your brain, which perceives the sound, turning it into what you hear. Connected to the cochlea is the vestibular system, this organ senses where your head is in space, and is responsible for your feeling of equilibrium.

The vestibular system, deep in your skull, is where your BPPV comes from. Within your vestibular system, there are a few parts. The first is the utricle and saccule, which are your otolith organs, the second important structure here are the three semicircular canals. These two systems work collaboratively to ensure you know where your head is in space at all times.

The otolith organs contain tiny calcium carbonate crystals, otoconia. Otoconia, often referred to as ‘ear crystals’, detect linear movement. They are “stuck” like rocks on jelly to a gelatinous layer, which is connected to hair cells. When you look down into neck flexion, the otoconia slide forward with gravity, which pull the hair cells forward, and transmit a signal to your brain via your vestibulocochlear nerve. This happens in all directions that would cause rocks to move with gravity. Through this mechanism, always know where our head is in space when moving linearly. Separately, angular movements like twisting, turning, and moving at an angle are detected by the semicircular canals. Three canals, anterior, horizontal, and posterior, detect motion within those planes. When the systems work together, you should always know where your head is in space.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo are:

- True room spinning/vertigo

- Vertigo that is only in certain positions & lasting less than 1 minute

- Vertigo sometimes associated with nausea and vomiting.

BPPV is frequently misdiagnosed in those who have other types of vertigo or experience chronic dizziness lasting longer than 1 minute.

Why Do I See the Room Spin?

Semicircular canals don’t just detect and transmit motion signals, they are also responsible for your vestibuloocular reflex, or VOR. VOR is the reflex involved with your keeping objects still while you are moving your head. When the vestibular system is working properly, you can easily look left and right, or up and down, quickly, while keeping your eyes still. You can experiment with this by choosing a spot on the wall to stare at, and shaking your head left and right.

VOR is important in order to maintain equilibrium, and our semicircular canals are responsible for making sure it works. When you look left, the fluid in your semicircular canals moves, stimulating the ampulla at the end of the semicircular canal in the plane of movement. That will cause a reflex to be sent through the vestibulocochlear nerve to your brain, to move your eyes in an equal and opposite direction. Then, if you turn back to the right, your eyes will move again, but to the left. This stillness is what keeps our gaze stable when we are walking, and helps us keep our eyes on objects even when we are moving around.

BPPV is what happens when there is an error in the system causing brief spontaneous nystagmus [involuntary eye movement]. The error that occurs is mechanical in nature, your otoconia move off their jelly layer into a semicircular canal. Most often, the otoconia slide into the left or right posterior canal. When this happens, you will experience vertigo that lasts 15-60 seconds and then stops until you move again. The most irritating times of day will likely be getting up in the morning, or going to bed at night. The act of laying down or rolling over in bed often places the canals in a dependent position. The dependent position will force the crystals to move and stimulate the receptors in the semicircular canal that is impacted. This causes the eye to move to correct for the head movement you’ve made. But instead of stopping like it would with your VOR as discussed above, the crystals keep moving because of gravity and inertia. When you have canalithiasis, otoconia are stuck in the canal, the nystagmus is very brief because the rocks settle in the canal and don’t move again until you move your head again. Your canals are sending a signal to your brain that says “we are still moving” even when you’ve stopped, which causes nystagmus.

Diagnosing BPPV:

BPPV is diagnosed based on nystagmus. Nystagmus is incredibly telling because it will move in a very specific direction based on the canal, and the place within the canal, that the otoconia are located. Otoconia can be located in a few different places. The first thing you need to determine is the canal in which the otoconia are residing. All testing for BPPV should be performed with Frenzel or Video Goggles to reduce fixation, an important factor in diagnosis. If your patient can fixate, he or she may be able to stop the nystagmus, which will give you a false negative and will make it more difficult to provide your patient a diagnosis.

It is logical to start by testing the most common canal, the posterior canal. This test is called the Dix-Hallpike (DH).

- Patient sits on the treatment table, close enough to the edge that their head will hang off if they lay backwards.

- Patient turns head to the right 30 degrees

- Patient quickly lays backward and extends head off the table into providers hands at about 45 degrees of extension

- Patient keeps eyes open, the provider watches eyes on screen or through goggles.

- Patient who has positive upsetting torsional nystagmus for 15-60 seconds is positive for Posterior Canal BPPV on the side the head is turned to in the Dix-Hallpike position.

- If positive for Posterior Canal Canalithiasis, treat with Epley Maneuver.

If both sides are negative in the Dix-Hallpike position, check the horizontal canals. To test the Horizontal canals, you perform a Supine-Head-Turn maneuver.

- Patient lays down with neck flexed to approximately 30 degrees, with either a pillow or with assistance of a provider.

- Head is quickly turned left (or right) and left in this position for 15-60 seconds, or until symptoms subside

- Patient keeps eyes open throughout the direction of the test, and the provider should observe eyes to determine the direction of the nystagmus.

- If nystagmus is geotropic, treat with a Bar-B-Cue maneuver to the direction opposite of the “more intense” nystagmus (if nystagmus is more intense on the left test, roll to the right), or try a Gufoni for geotropic nystagmus.

- If nystagmus is ageotropic, treat with Bar-B-Cue maneuver to the direction of the “more intense” nystagmus (if nystagmus is more intense to the right, roll to the right), or try a Gufoni for ageotropic nystagmus.

If all 4 canals are negative for BPPV, but the patient’s subjective interview really makes it seem like BPPV, test for the anterior canal. The head hanging test is for the anterior canal.

- Place the patient on the table close enough to the edge so when they lay back, their head will hang off the edge into providers hands

- Lay back quickly into cervical extension, look for nystagmus.

- Positive test will show down beating nystagmus (with potential torsion) toward the affected ear.

What is the Difference Between Cupulolithiasis and Canalithiasis?

Diagnosing BPPV is the act of determining where the otoconia are stuck within the vestibular system. Otoconia can be misplaced into six different places in either ear. You must determine the affected ear, the canal, and then if it is in the cupula or canal. Within the vestibular system, pictured above, there are the semicircular canals and the ampulla, which houses the cupula. Canalithiasis refers to the otoconia stuck in the semicircular canals. Cupulolithiasis refers to when the otoconia are stuck in the ampullary cupula.

This direction and duration of the nystagmus determines whether you have cupulothiasis or canalithiasis. See the guidelines below for features of each kind of nystagmus and the corresponding diagnosis.

- Right up-beating torsional nystagmus in Right DH position: positive for right posterior canal canalithiasis

- Left up-beating torsional nystagmus in Left DH position: positive for left posterior canal canalithiasis

- Geotropic nystagmus that is more intense in the Left Head-Roll position: positive for left horizontal canal canalithiasis

- Geotropic nystagmus that is more intense in the Right Head-Roll position: positive for right horizontal canal canalithiasis

- Ageotropic nystagmus that is less intense in the Left Head-Roll position lasting >60s: positive for left horizontal canal cupulolithiasis

- Ageotropic nystagmus that is less intense in the Right Head-Roll position lasting >60s: positive for right horizontal canal cupulolithiasis

- Down-beating nystagmus in a head hanging position: positive for ageotropic canal canalithiasis

How to Treat BPPV

Once the correct canal is diagnosed, treatment is relatively simple. Because the otoconia respond to gravity and have likely just slipped into the wrong place, they can be rolled back out, into your otolith organ. The treatment you should receive is completely dependent on the canal that is being affected. Your physical therapist will determine this via a series of tests and watching your nystagmus, the exact diagnosis, and the direction in which you will need to be treated.

- For Posterior Canal Canalithiasis BPPV, you will need to be treated with an Epley Maneuver.

- For Horizontal Canal Canalithiasis BPPV you will need a Bar-B-Cue roll or a Apiani maneuver.

- For Horizontal Canal Cupulolithiasis BPPV you will need a Casani maneuver.

- And for Anterior canal BPPV, you will need a head hanging maneuver.

No matter the kind of BPPV you are experiencing, or how it is treated, it is most important that a professional help assist you with the maneuver. When performed independently, I have found that often times patients put the already displaced otoconia into another canal, instead of back into the otolith organs. Although it is still treatable, it does become more difficult; it is recommended you seek treatment from a physical therapist or ENT first.

Why Me?

Annually, about 1.6% of the population gets BPPV, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%, making It a very prevalent condition (1). Once diagnosed, it is possible that thee BPPV will recur again in the next few years. Although vertigo can be scary and anxiety provoking, once you know what it is, it is easier to self-diagnose and seek proper treatment. Fortunately, it can be treated easily through Canalith Repositioning Treatments as listed above.

Physical Therapy for BPPV

Physical therapists are the main providers who perform Canalith Repositioning Maneuvers, so with BPPV, physical therapists are vital to your treatment! If you are pretty sure this is what’s going on, make an appointment with a vestibular PT today. He or she will evaluate you completely, determine the canal and source of your dizziness, and treat you accordingly! You have direct access to a physical therapist in all 50 states (find one here!), so no need to make an appointment with your primary care physician first.

Source:

(1) Fife, T. D. (2017). Dizziness in the Outpatient Care Setting. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, 23(2), 359-395. doi:10.1212/con.0000000000000450. https://journals.lww.com/continuum/Fulltext/2017/04000/Dizziness_in_the_Outpatient_Care_Setting.7.aspx

Let’s face it, being dizzy can be really scary, and therefore, really anxiety provoking. Anxiety and dizziness go hand-in-hand, when I talk to my patients about this, I compare them to best friends. They love to be around each other, they relate to each other, and when one acts the other reacts. It creates a cycle that goes around and around, usually until the dizziness stops. Vestibular disorders, although invisible to others, cause real physical symptoms of dizziness. These symptoms provoke anxiety and frequently cause anxious behavior, and for patients with vestibular dysfunction this is normal. For those with anxiety surrounding their vestibular disorder, we can work together in physical therapy to treat the root cause.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Dizziness related to anxiety can be a result of another kind of dizziness or vertigo that then feeds on your anxiety symptoms. Alternatively your dizziness can be a result of an anxiety disorder. However, in most cases I find that my patients have a combination of both happening. The most difficult thing for patients is often breaking your cycle of dizziness and anxiety.

Treatment

Because your dizziness and anxiety cause each other, we need to break the cycle in one or the other. If your dizziness has a root cause, like BPPV or Vestibular Neuritis, we can treat the source of your dizzy symptoms, hopefully relieving some or all of your anxiety. To treat these, we can use exercises for you

Vestibular Ocular Reflex (VOR), an Epley maneuver, or optokinetic stimulation. If anxiety is increasing your symptoms, or is the source of your symptoms, we need to find you a way to stop those feelings. Treatments to help decrease feelings of dizziness and anxiety are meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and grounding.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy is a vital part of your journey toward dizziness relief, your vestibular therapist can help through a variety of treatments. One way to help anxiety through physical therapy is called grounding. There are a few ways you can do grounding, but my favorite is performed in a nice arm chair; if you don’t have an armchair, you can use a chair without arms as well! This kind of grounding is specifically for those with dizziness. Step one (1) sit in a big, sturdy chair, with your feet on the floor and arms on the arms of your chair. Step two (2) place 1 hand on your belly and the other on your chest; breathe diaphragmatically into your stomach. Step three (3) shut your eyes and begin to feel how still your body is. Start at your feet, feel how still the floor is; next feel the back of your legs on your chair and how still you are. Repeat with your arms, back, and maybe even your head! Continue to breathe deeply and evenly into your diaphragm. Continue this for 5-10 minutes until your anxiety and dizziness symptoms decrease.

Your physical therapist may recommend grounding, or may recommend another form of treatment to help with your anxiety. These may include a referral to a therapist or counselor, dietary recommendations and considerations, or vestibular exercises to treat the root of the issue. A discussion of a well-rounded, holistic plan specifically for you is the best way to act on your anxiety and break the cycle.

PS: if you made it to the end of this article and you’re in the holiday challenge, send me a DM for 2 extra points!