Although there is a distinct difference between these two inner ear conditions, one can play a role in the other occurring. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo or BPPV is a type of true, room-spinning, vertigo caused by the displacement of otoconia from your otolith organs within your inner ear. Endolymphatic Hydrops, both Primary and Secondary, is related to a pressure-volume issue in the membranous part of your inner ear, which causes dizziness, sometimes vertigo, ear fullness, hearing loss, and more.

Before we get into the relationship between the two conditions, let’s understand what’s happening in each diagnosis.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV is the most common form of vertigo, and most of the time we have no idea why it happens. Tiny ear crystals, otoconia, fall out of the space they belong and into the semicircular canals, most commonly the posterior canal. When this happens, the otoconia sliding through the canals when you move your head causes nystagmus, or involuntary eye movement. This nystagmus then makes it look like the room is spinning. If you’d like more info on BPPV and nystagmus, click here.

Primary and Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops

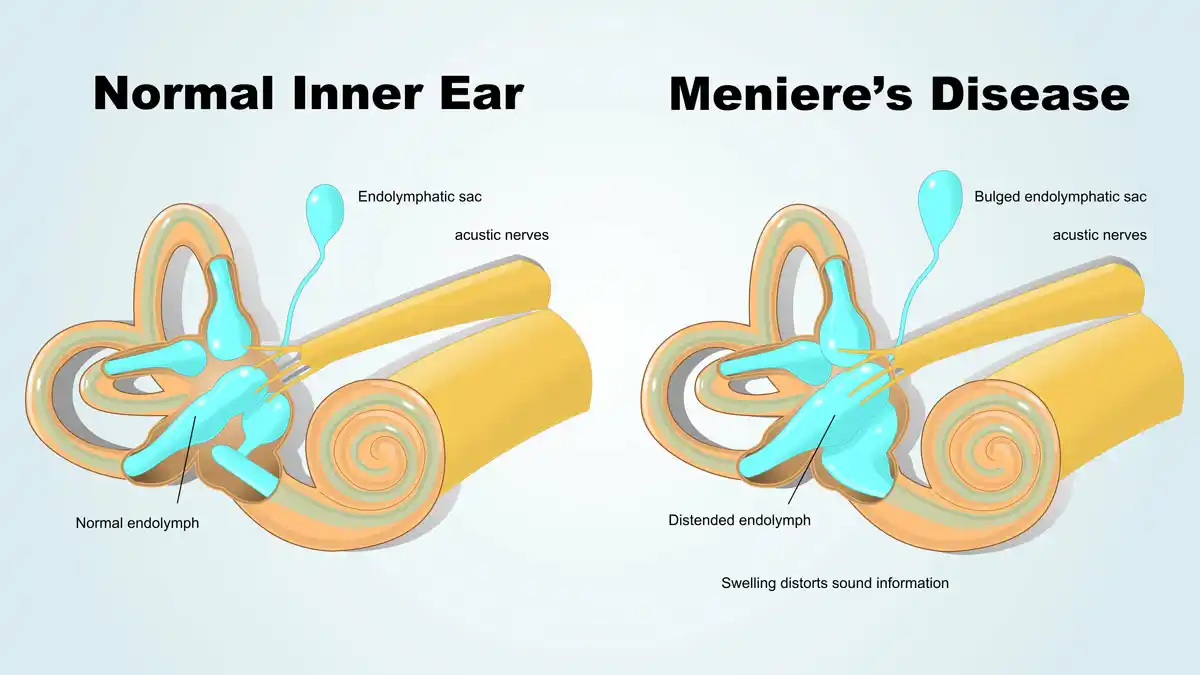

Primary Endolymphatic Hydrops, AKA Meniere’s Disease, and Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops are a result of an inner-ear pressure-volume relationship dysfunction. Endolymph is the fluid within your ear canal, it is high in sodium, and water osmoses between the endolymph and the perilymph on the other side. When there is too much fluid, because of the laws of physics, more fluid goes toward the endolymphatic portion of the inner ear, causing swelling of the endolymphatic membrane.

In the photo below, you can see two distinct colors. The first is the brown color – that is the bony labyrinth – this depicts where perilymph, the fluid high in potassium, resides. The pinker color illustrates where the endolymph is. Not pictured is the endolymphatic sac, a large protrusion toward the semicircular canals, that acts as a residual area for endolymph to swell. This swelling can push up against the vestibular nerve, causing hearing loss and dizziness. Additionally, the swelling due to an imbalance, that is not corrected quickly, can cause BPPV.

Why Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo?

BPPV and Endolymphatic hydrops are related because the pressure fluctuation that happens during an episode of Endolymphatic Hydrops causes the otoconia to fall ‘out’ of the organs where they belong. There is not a lot of research that has been done to back up this information. There is some info, which I will cite throughout the rest of this article, but nothing that is totally evidence-based to back up this information. However, anecdotally, I see this quite frequently in my practice, and many other clinicians do as well, and there are a few theories.

Evidence for BPPV in Patients with Meniere’s Disease

This article, is a case review of 162 people, 9 of whom absolutely have Meniere’s Disease and the remaining had some reason to believe they did. This article only focuses on the 9 people with absolute Meniere’s Disease diagnoses, and within those 9 people, all had BPPV affect their ear, and one bilaterally. This shows that when you have Meniere’s Disease you’re more likely to have BPPV in that affected ear.

This article states two important pieces of information. The first is that most of the time, people who get BPPV have no underlying ear condition – it just happens at random. This is good because it really decreases the number of people we need to consider having vestibular conditions. However, it also states an important fact, which is that people who do have underlying vestibular conditions are more likely to have BPPV. It’s important to recognize this because knowing that you may have BPPV can make it less frightening if and when it happens. Additionally, it also states that inner ear diseases can indeed be to blame for detaching otoconia from where they belong.

The last article I will mention here is the closest I can find to solid research, rather than case studies, on this issue. This article talks about the different vestibular pathologies causing BPPV and the likelihood that BPPV is caused by a primary vestibular disorder, which in this case is referred to as Secondary BPPV. Secondary BPPV is likely underdiagnosed in comparison to Primary BPPV. This is because we often just treat the BPPV with an Epley, or other, maneuver and then not look into it further, even when it is recurring. However, if your BPPV is recurring, it’s so important to look deeper into how you could prevent this.

How do We Prevent BPPV?

Secondary BPPV is the term used to describe BPPV that’s occurring because of an underlying condition. By definition, your vestibular condition must be on the same side as where you have BPPV. So, if you have Meniere’s Disease, you’re more likely to have BPPV on the side where your Meniere’s Disease is as well. The same thing goes for Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops, Vestibular Migraine, and Vestibular Neuritis. Preventing BPPV is not really possible in primary BPPV, because by definition it happens for no reason, but if there is a relationship between Meniere’s Disease, Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops, or another vestibular condition you may have control over this.

Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops is different from Primary (AKA Meniere’s Disease) because it is more predictable and not as degenerative as Meniere’s Disease. Preventing a flare of either though can be a challenge. Here are some tips:

Meniere’s Disease Prevention:

- Eat a low sodium diet

- Eat a low sugar diet

- Avoid caffeine

- Avoid alcohol

- Exercise regularly

- Medication

- Stay hydrated

- Track the weather patterns

Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops:

- All of the above, but track your triggers

- Tracking your triggers is important with Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops as you will be able to see what flares up your vestibular system most.

- Check in about allergies

Again, Secondary Endolymphatic Hydrops is simpler to control than Meniere’s Disease, and although not simple, tracking your triggers will help you determine what may be causing the recurrent BPPV.

Other Causes of Secondary BPPV:

Vestibular Migraine: “the prevalence of migraine in patients with BPPV was twice as high as that in age- and sex-matched controls”

Vestibular Neuritis: “The incidence of vestibular neuritis among BPPV patients has been reported within the wide range of 0.8–24.1%”